I am a writer. To me that sounds very simple, and when it comes up in conversation with a real human being I’m able to elaborate with fluidity and ease that I’ve written one book, that I have a second one in the works, that I write short, thousand-word-ish think pieces on culture and society every couple of weeks on my website. My fields of interest and study are such and such, my work includes so on and so forth, and at that point the conversation will go in one of a few dozen directions and things will go on the way that they do when you deal with an actual living person.

But trying to have that same conversation with a small light next to a little lens, so that you can put it on a dedicated corner of the internet, so that it can be waved in front of whoever should take an interest in what you have to say feels acutely disingenuous, or at least it does to me, and if you stare into that little light for long enough, trying to to figure out how to be “authentic” while attempting to boost traffic and drive subscriptions, you can begin to wonder what on earth it is that you’re doing.

The questions that test a writer these days, at least in the context of publishing, aren’t things like, Have you broken new ground? Will you make people think? or, Have you contributed something of value to human society? They’re, What is your platform like? Do you drive “engagement” on your “content”? How many followers do you “reach”?, and, Have you mastered the post-to-repost ratio on Twitter?

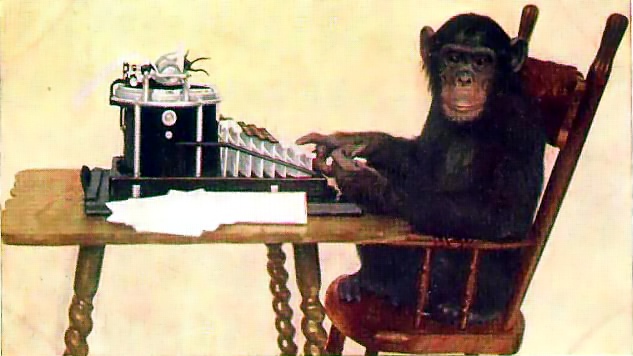

Until the last five or ten years, writers didn’t to have to stir up a “following,” to which they provided “content,” generating “interest,” so that they could “market” effectively to their “core audience.” I know this because the social networking sites on which these things are based didn’t exist five and ten years ago. Has everyone forgotten that people used to build things called reputations, based on their efforts, which had merit, and their work was shared genuinely because of what it had to communicate and because of the quality of that expression? (I have a hard time imagining what might have been the “social media platform” of guys like John Steinbeck or Kingsley Amis or John Kennedy Toole, or for that matter guys like Isaac Newton or Charles Darwin.)

It’s like the job description changed at some point along the way and nobody let me know before I got busy trying to write things that deserve to be read, and it’s impossible to escape the fact that my work itself is the last thing that has anything to do with the process of developing a “social media presence,” and creating a “marketing strategy”.

I’ve written before about celebrity authors and ultra-bestsellers, and the sort of greased rail that these things ride into noteworthy status (in some cases, even existence), but it’s getting to be more and more that that’s what the publishing industry is demanding rather than just occasionally exploiting. In this age where people can become famous without doing anything, we are now encouraging a literary and publishing atmosphere where you must become famous before you can do anything.

When you’re trying to get published, they ask you where you’ve been published. When you’re trying to contribute to a field, they ask you how you’ve contributed to that field. When you try to establish yourself as an authority on a particular topic, they ask you how you’ve established yourself as an authority on that particular topic. It all comes down to risk, and the companies now want to take as little as possible.

So what about self-publishing? Isn’t that the 21st century’s answer to the oppressive bottlenecks of the publishing establishment? Maybe, but only if you have money to burn.

In terms of simply getting physical copies of one’s book printed, independent authors have a lot of options these days, but not ones that are competitive, or in some cases even sustainable. Print On-Demand systems, like the Espresso Book Machine installed at dozens of independent bookstores around the world, are becoming more common, but the standard costs can be $10 per book for a work around 200 pages. If you can afford a bulk order, you can do short-run printing for around $6-8/book for 100 of the same size. Traditional publishing houses on the other hand can print a comparable book for about $3, and they only ever spend more printing Advance Reader’s Copies (ARCs), or “galleys” as they’re sometimes called, so if a book sells for around $14 (basically the going rate for a 200-page black and white paperback), you can see that the margins for a self-publisher can be anywhere from 20-50% worse just on the printing costs.

If you want to get your books in stores you have to sell them for between 60 and 75% of the cover price so that the bookstore can make their money, so you’re often selling the book for $8.50-$10.50, even if it cost $9 or $10 to produce. This means that to recoup the hundreds of dollars that you spent getting the book prepared (editing, proofreading, ISBN registration, research costs, indexing if it’s nonfiction) you might have to sell hundreds or thousands of books this way before you even start turning a profit. You can set the initial price higher of course, but you’ll find that if they do sell, they sell much more slowly than they should.

What’s more, a surprising number of local and independent bookstores out there deal only in used books, some may only want to buy on consignment which means that you have to wait to get paid until your books have sold, and some may not buy self-published books at all. Large-scale distribution becomes absurd rather quickly at these margins, and even if you could afford it major chains are unlikely to carry an independent work because they rely on large supply networks to maintain consistency throughout their stores and as a consequence they mostly order from the catalogs of publishers.

If you try just to sell digital copies, for example on Amazon’s Kindle Direct Press, it doesn’t get much better because Amazon takes the lion’s share of the sales, they charge fees on top of that, and you have to set the price very low in the first place because that’s what Amazon and its customers are about, so between those three things you’re lucky to make a dollar or two per sale. On top of that, those sales are hard to come by because you’re competing with the 33 million books that they stock, because those recommendation engines analyze buying patterns, not content, and because online shoppers tend to know what they want to buy in the first place.

So what about crowdfunding? Don’t sites like Kickstarter and IndieGoGo allow you to build an audience and raise money at the same time? In short, no.

I really loved crowdfunding as a concept, and there was a time when it first came out that it was really exciting, but these days there are just so many projects going that it’s tough for anything that doesn’t already have a connected audience to get any attention. I got fed up with Kickstarter because they don’t do anything to promote your project, even things as basic as making sure that projects with 3 days left show up on the home pages before projects with 30 days left or making sure that projects that haven’t reached their goals show up before projects that have, so it’s easy for a project to get buried a few pages down in the search and browsing results and never move.

The other problem with crowdfunding is that essentially a lot of it has turned into a kind of pre-order gadget shopping, which is fine and there are a lot of great things out there, but projects like that are very different because they have a prototype and a timeline and people can imagine that thing as it will be when they get it, versus a film or a book project where it may take a relatively long time to make an end product that they may or may not like. Even CD release projects from musicians have an advantage because it’s easy to upload a track or two, or people can come see your band live, and they can get a sense of whether they’d like to fund your record. Those are the kinds of things for which crowdfunding works and other projects are less attractive in that context; if someone with a limited budget is looking to fund a project or two it’s more likely that they’ll go for the things they can reasonably expect to be satisfying.

All of this is to say that, in more ways than one, the lines between artist, showman, businessman, and evangelist haven’t been blurred, they’ve been shattered. These days every new writer in America has to conduct themselves in a manner that was once reserved for infomercial jockeys and shameless self-help pseudogurus, and this is bad. It’s not just bad for me because I’m personally averse to the second half of that equation; it’s bad for writing, it’s bad for the culture, and ultimately it’s bad for the society.

Publishers have decided that the key to making their business a profitable one is to fire all the people who are good at doing things that make books sell and to lump all of those things onto the people are supposed to be making books. It’s as if an entire industry started forcing the sword into obsolescence because it doesn’t come with a corkscrew, nail-clippers, and a set of pliers attached to it, and that mentality is trying to drag down everything that goes with it. I am not a salesman, I am not an entrepreneur, and even though that sounds like an admission of failure in this day and age, you can’t say that being either of those things would make me a better writer, which if you ask me is the sort of thing that writers should care about.

Could you imagine taking a Van Gogh, and saying we’ll put this painting on the busiest street corner we can find, and we want the painter to stand in front of it 24 hours a day so they can flag down pedestrians and try and get a few bucks out of them to justify the painting’s existence, and then if he makes enough money we’ll give him some food and he can make more paintings? What makes these publishers think that the skills required for these two jobs are even remotely similar? You probably couldn’t get someone who was less adapted for this 21st-century garden variety of fame, and if I have to explain his importance as a painter you’ll probably never understand what I have to say.

The ridiculous phrase that you hear constantly is that, “these days you are just as important as your writing.” Let me be very clear, what these business people don’t understand is that an author is their writing, and there was a time when that used to matter. For the life of me I couldn’t figure out, as I stared blankly into the small light on the camera, just what on Earth making punchy, eye-catching videos (or for that matter tossing out little blurbs on Twitter) had to do with my chosen profession which, let’s face it, is somewhat inherently anti-social. I don’t want Twitter followers or YouTube hits, I want my work to be well regarded, and if anything I want to be invisible in that process, not more visible.

But the biggest problem with all of this, and the one that is the most fundamentally dangerous, is that it undermines the relationship that the arts have to society, which should always be something close to adversarial. Bullshit is the artist’s natural enemy, their duty is to the truth, and you fuck with that relationship at the society’s peril. Artists, more than anyone else in society, have to reserve the rights not to please crowds, not to smile, and above all, not to be popular. In other words, an artist must be allowed to dismiss the public’s friendship so that they can fulfill their duty as its ally.

When the barrier to entry in the writing business becomes popularity then only popular people with popular thoughts and popular ideas will be published, and everything that fits in the gap between what makes something popular and what makes something valuable will dissolve. When the business people get done with the arts, all that’s left will be entertainment.

Books are products, yes, but they are a product unlike any other because they are the purest vessel that we have for ideas and, though it would be impossible to convince the industry of this, the shadow of book’s substance that it is even possible to market is almost purely incidental to the process. Books are fundamentally about thoroughness and patience, and it’s absurd for the industry that sells them to have become so reliant on things that involve neither. It’s absurd for things that are meant to last for centuries to be ruled by things as ephemeral and vacuous as “buzz”. And it’s absurd for my career as a writer to be more threatened by Twitter block than by writer’s block.